© Catharine Ellis, as posted to the blog: Natural Dye: Experiments and Results

On this blog site, I have previously written about the indigo fermentation vats in very general terms. I have been using these fermentation vats exclusively for over 5 years now and I feel strongly that it is the best approach to use for indigo dyeing. So, I have made the decision that I would like to share much more specific information regarding how to make and maintain these vats through a series of posts in coming weeks. I hope to roll a new one out every few days days or so.

Since I began the transition to using ONLY natural dyes in 2008, I have continued to learn and to refine my practice. Dyeing with indigo has been one of the most rewarding, yet challenging adventures. Striving for, and practicing a level of mastery related to indigo dyeing, is necessary to achieve a full palette of color using natural dyes and having the ability to control shades of indigo blue is a necessary skill.

In the 1970s, I did my first indigo dyeing using sodium hydrosulfite as a reduction agent for my vat. I never liked dealing with the reducing chemicals, such as sodium hydrosulfite or thiourea dioxide. The smell was off-putting and, more importantly, I had concerns regarding the safety of such chemicals. I abandoned their use (and indigo dyeing) until many years later.

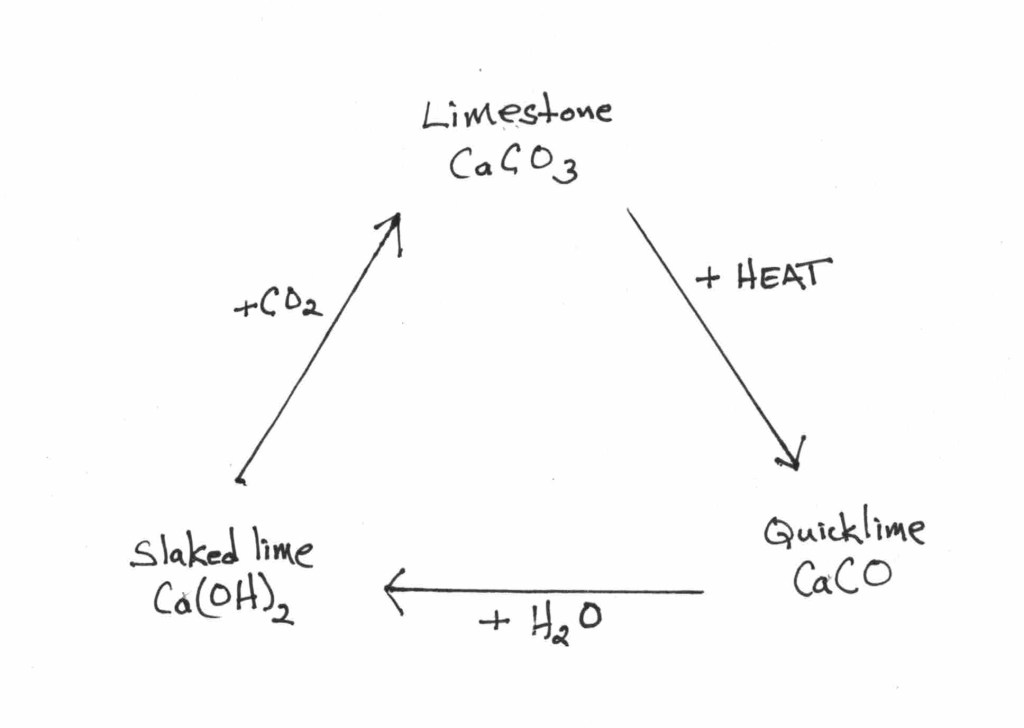

I was thrilled when I learned from Michel Garcia that indigo vats could be made using benign substances such as sugars, plants, ferrous sulfate, and lime (calcium hydroxide) which I was able to purchase in the grocery store as “pickling lime”. Vats made this way are considered to be, or described as, “quick reduction” vats. They reduce and are ready for dyeing within hours and can be maintained for an extended period with proper attention. I was very happy. These are the vats that Joy and I included in our book “The Art and Science of Natural Dyes”. I believe that these are still the best vats for short term dyeing workshops and other situations where a working vat is required quickly.

Over time, though, I observed that there are issues and challenges with these vats.

Crocking (the rubbing off of color) was a problem, despite proper finishing and washing, and especially when dealing with knitting or weaving yarns, which are handled a great deal. All indigo dye seems to exhibit poor resistance to rubbing to some extent, but the quick reduction vats seems to crock more. What I understand is that excess calcium may react with the reduced indigo and makes it into insoluble compound. These vats depend on the use of large quantities of calcium (calcium hydroxide). I am now thinking that it is possibly the reason for the bad rubbing fastness or crocking.

The color often faded inexplicably, turning pale and displaying washed out areas, or just completely disappearing. I have observed this occurred where cloth was folded and put away on the shelf. Even when a textile was rolled up and stored in the dark, I would find that the blue had literally disappeared in some parts of a textile despite careful finishing and neutralization. I’ve had discussions with other dyers who have also experienced this same phenomenon, so I know I am not the only one who took note. I always do lightfast test on the dyes that I choose to use for my work but this was something else entirely

In 2017 I began my journey using indigo vats that reduce by the activity of fermentation after meeting Hisako Sumi, Japanese indigo dyer and researcher. Hisako encouraged me, guided me, and even put together and gifted me a small “kit” which she mailed from Japan, so that I could start my first fermented vat. I began experimenting, testing, dyeing, observing, and never looked back. Hisako generously ‘coached” and mentored me from from her home in in Hokkaido and provided me with a much deeper understanding of my vats.

The COVID pandemic kept many of us home for long stretches of time, and during that period many of us learned new skills or honed old ones. That time provided me the opportunity and focus to tend indigo vats and to develop and refine an understanding of the fermentation process. My indigo dyed textiles have never been better! I no longer fret over potential “unexplained” fading. The quick fermentation vats require high alkalinity (pH 12). The fermented vats are able to be maintained at a lower pH than the quick reduction vats (pH 9.5-11). This is accomplished by the use of wood ash lye, soda ash, OR potash to achieve the correct pH. I have used all of these alkaline sources successfully. Lime (calcium hydroxide) is used in very small amounts and only to “tweak” the pH maintain desired levels. The lower alkalinity of the fermented vats is more suitable for all fibers. I will likely never return to quick reduction vats, unless specific circumstances require their use.

In some of my previous blog posts, I have written about this process in general terms and also have given credit to Cheryl Kolander, whose online recipe was a good starting point for me, but until this time, I was not ready to publish anything definitive of my own. In fact, I have never published an “actual” recipe on my blog: Natural Dye: Experiments and Results.

I am not a trained scientist/chemist, but through experimenting and multiple observations I have done my best to understand what happens in the fermented indigo vat so that I can use and maintain the vat. And now it is time to share that specific information and information about the process I have used. Over the coming weeks (and about a dozen blog posts) I hope to “walk through” the planning/making/maintaining of a fermented vat and to encourage and guide dyers to explore on their own. And, as we approach summer in the northern hemisphere, it is a good time to try these vats. But do keep in mind, fermentation vats may not be the best for a beginning dyer or for someone who does not have the time and focus for it.

One does not do this alone. I owe much to Hisako Sumi, Michel Garcia, Joy Boutrup, Dr. Kim Borges of Warren Wilson College, and to all my colleagues and students who have been willing to experiment with me.

As a dyeing community, perhaps we can all help each other to learn, understand, and to work through the process of indigo fermentation. Your comments are most welcome. My goal is to start that process with a series of blog posts that might help you begin your own journey. By all means, if you have a “dye mentor”, do consult them! I don’t have all the answers but maybe we can get there together.

As always Catharine, I am so very grateful for your contributions and generous sharing of your experiences. Thank you! I too have experienced that textiles dyed in my fermentation vat (using a slight derivation of Cheryl’s online recipe) using my homegrown indigo pigment, spent madder root, some wheat bran and soda ash) have fared incredibly well over time with no fading at the folds or direct oxygen exposed areas as I have experienced with my quick reduction vat dyed textiles.

And I have been especially impressed with the incredible depth of blue I have achieved with my homegrown indigo pigment in my fermentation vat- even in cases where the pigment is seemingly “lower quality” or lighter blue/ gray blue in color because of extra calcium hydroxide using in the floccing of the pigment in the aqueous extraction process.

One thing I have noticed is that my iron vat quick reduction vats as well as my “whole fruit” vats seem to also fare better than my fructose vat dyed textiles. Have you noticed any difference in your textiles dyed in iron/henna/walnut vats?

I’m currently in Japan for a fermented vat Indigo Study and feeling inspired as ever to keep up a fermentation vat practice. The hardest part I have found is keeping my pH meter calibrated and in good working condition as well as keeping the outer water bath at the right temperature for the happiest living bacteria vat. I’m thinking this year I want to start a new vat with a different heating situation that is more reliable and possibly more energy efficient.

How wonderful to hear you’re now able to spend plenty of time with your grand babe. Wishing you much love and very much looking forward to your future posts!

thank you again!!

-Liz Spencer