I welcome the opportunity to teach a workshop, especially when it will teach ME something new.

A few days ago I taught Dyes from the Local Food Co-op at Cloth Fiber Workshop in Asheville. The class came about when I was measuring some herbs and spices at our local food co-op. I noticed that a number of the dried materials in the glass jars were the same as the dye plants I was using in my studio: buckthorn bark, annatto, chamomile, and dock root. Obviously, the co-op was not stocking these substances for dyers, but….. it caused me to think about the multiple uses of these plants. For many years I have been taking a tincture of Isatis tinctoria, or WOAD, prescribed by my Chinese medicine doctor. How much overlap would I find between the dye and culinary/medicinal plants?

After taking an inventory of the materials available at the local co-op I decided on a collection of plants for this class. The criteria for the dyes included the following:

- Each plant has some historical reference as a dye plant, and is preferably included in Natural Dyes: Sources, Tradition, Technology, and Science by Dominique Cardon.

- Each has an alternative use, such as medicinal or culinary.

Not all of these dyes are excellent performers. For reasons of poor light fastness or wash fastness I would not choose to use many of them in my regular studio work. But each dye has a story and may have been used throughout history because of its striking hue, availability, and/or affordability, despite a poor performance as a color over time.

Some of the dyes have been assigned a Natural Color Index Number (CI#). This is a reference database of color hues, names, and products maintained by the Society of Dyers and Colorists and the American Association of Textile Chemist and Colorists. It includes both synthetic and natural pigments. The inclusion of these natural colorants confirms the important historical reference and unique quality of their colors.

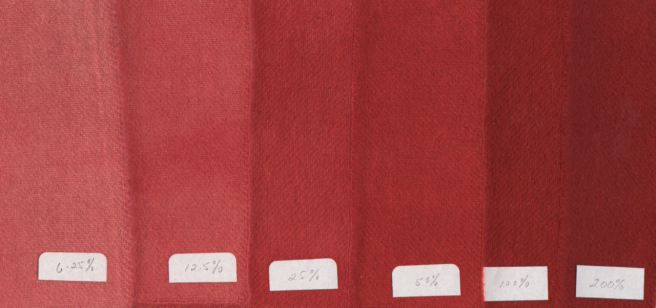

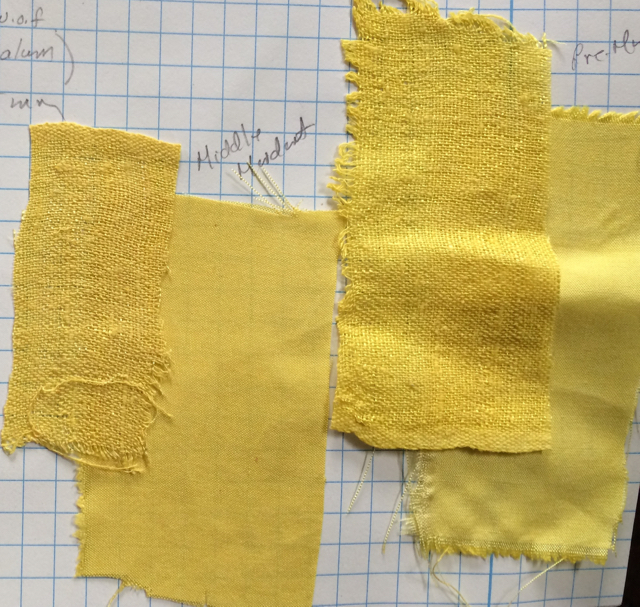

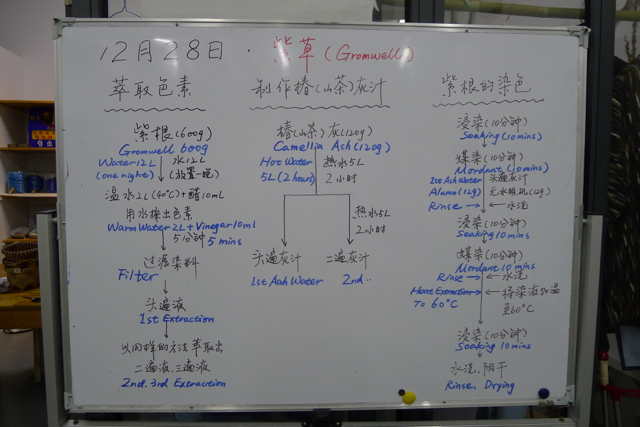

Our dyeing was done on silk fabric. Some dyes required mordants, while others did not. Some roots and barks required alcohol extractions, while others extracted in water. Some dyes were affected by alkalinity. Others contained tannins and were altered with ferrous acetate. Alternative sources of the same plant resulted in color variations, suggesting that different parts of the plant were used, or possible changes in the growing season or drying process. When appropriate, we used alternative methods of dyeing such as a one-bath acid dye or fermentation.

The dyes we used:

- Alkanet, Alkanna tinctoria

- Annatto, Bixa orellana

- Avocado pit, Persea americana

- Black Walnut, Juglans nigra

- Bloodroot, Sanguinaria canadensis

- Buckthorn, Rhamnus frangula

- Chamomile, Matricaria chamomilla

- Cloves, Syzygium aromaticum

- Dock root, Rumex crispus

- Eucalyptus leaf, Eucalyptus gunni

- Goldenrod, Solidago canidensis

- Henna, Lawsonia intermis

- Mahonia, Mahonia aquifolium

- Rhubarb root, Rheum officionale

- Sandalwood, Pterocarpus santalinus

- Sassafras bark, Sassafras albidum

- St. John’s Wort, Hypericum perforatum

- Turmeric, Curcuma longa

The exploration of natural dye continues….

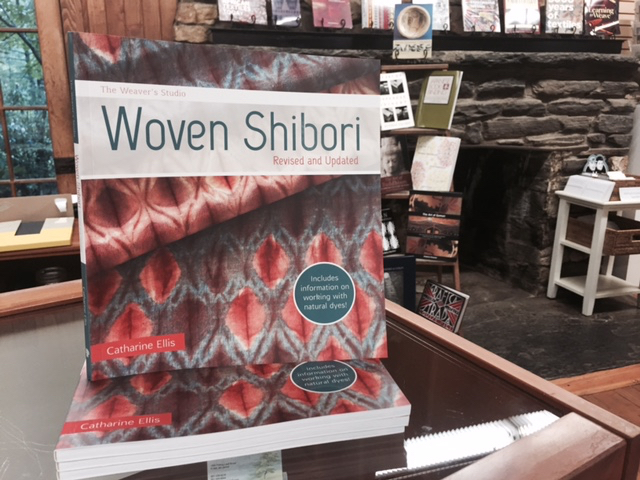

Woven Shibori with natural dyes is here!