I’m on Cape Cod right now, taking a retreat of sorts at our family home to finish work on a new edition of Woven Shibori, focused on natural dyes.

I’m a great fan of the local public radio station here, WCAI. This week I listened to Robert Finch, a naturalist and nature writer who I admire a lot. He does a regular broadcast: A Cape Cod Notebook. The topic this week was “When did you decide you wanted to be a writer and why?” It was quite relevant since I’ve been sitting at the computer for hours each day working out all of the myriad details of the book. Finch told us that his reason for writing was “to play” and to “keep play at the center” of his life.

I could identify. Textiles and dyeing have been a passion, a career, a livelihood, but it really does feel like “play”. I get up in the morning, go to the studio, and discover something new through experimenting, thinking, observing and “playing”. It’s serious play, but that’s why it is so satisfying. How fortunate I am!

I have no studio on the Cape so I don’t accomplish serious weaving or dye work here but this place has introduced me to one aspect of natural dye: lichens. The woods behind the house are full of trees and those trees are laden with lichen. Each time I come here I pick up branches that have fallen from the trees. They are covered with both foliose and fruiticose lichens.

Recently someone told me that the lichen was “killing the trees” here. I don’t think that is the case. The trees are old and branches die. As the canopy diminishes, the light is able to penetrate, making it a more hospitable place for the lichen to grow. The lichen grows best on the old branches without foliage. The branches finally give way, falling to the ground covered with lichen. This is the only lichen dyestuff I gather.

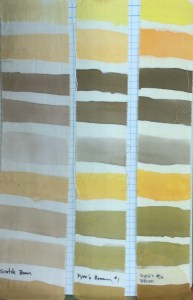

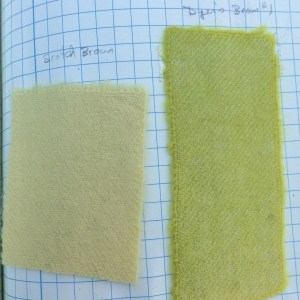

These are “boiling water “ lichens that, after simmering in water (no mordant), will dye wool (protein) various shades of yellow and gold. The dyes are extremely fast to light and washing.

Lichen is an indicator of clean air. They don’t grow where there is lots of air pollution or car exhaust. Lichens are complicated. They are both an algae and a fungus. Karen Casselman has written a good book about lichen dyeing, Lichen Dyes, the New Sourcebook. I have taken classes on lichens at our arboretum where we learned a lot of technical information about identification. There is more to know than I could ever hope to absorb.

Mostly I like to walk in the forest on the Cape and pick up lichen that I find along the path. I bring it home and scrape it off the branches. I put it in a net bag, cover it with water, add some wool and then simmer for a good long time. The first sign that something is happening is the smell – deep, woodsy, and rich. That smell permeates the wool fiber and stays for a very long time in the wool. I have been told that lichens will leave a yarn mothproofed. I can’t prove that but I have yarns that were dyed years ago that still have that woodsy smell in them. The color is slow to come, but eventually a light beige color will appear, which will get darker and more gold with time and simmering. The various lichens will result in different shades of gold and brown.

Lichen is very slow growing. I would not consider harvesting living lichen. But once it falls to the ground it will begin to deteriorate.

There is another class of dye lichen – the orchil lichens: Umbilicaria mammulata and Umbilicaria papalusa. They grow on rocks at high elevations where I live in NC. They are even slower growing and should never be harvested from the rocks. Occasionally I will find a piece that has fallen to the ground and bring it home for dyeing. This type of lichen needs to be fermented in ammonia for several weeks. It will dye wool an intense purple but the color is not lightfast and will quickly disappear.

I don’t use lichens as part of my regular dye production or work. They are a special treat. This type of dyeing is truly “play”. I use them for my own pleasure and to remind me of the walk in the woods that brought them into my path. They are too rare to be able to count on or be available commercially. The windfall gifts are my special pleasure from the woods.