I’ve been using a lot of madder. I have madder roots from my own garden and extracts on the shelf, but right now I’m focused on the fabulous ground Rubia cordifolia from India that I purchased from Maiwa. It’s ground very, very fine. Charllotte tells me that it’s ground on a mill stone.

Because the particles are so small, the dye is extracted more easily than from chopped madder root. The color is redder than I would expect from a rubia cordifolia. I love it!

Once the fibers are mordanted correctly I’ve usually been content to make a full strength dye bath. There is always leftover dye in the bath, which most often gets turned into a dye lake. I didn’t have a full understanding of how much dye was actually in the dye pot or what remained after the initial dyeing. In order to control my colors and mix them effectively I needed a clearer picture of dye strength and hue.

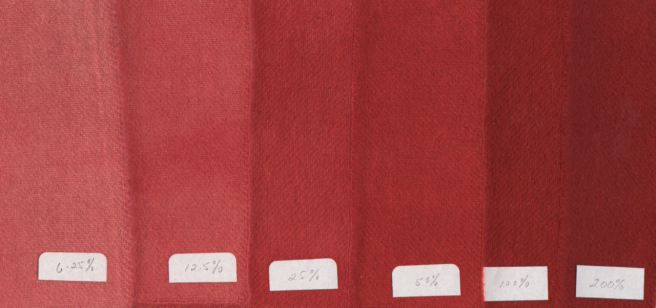

I embarked on a systematic observation of the dye. The fiber was linen. It was treated with tannin and mordanted with aluminum acetate. I weighed out the total amount of dye that was needed for my various samples. Typically I do 2-3 extractions in order to make my dye bath but this time I decided to continue extracting until there appeared to be no more color coming from the ground root. This took SIX 20 minute extractions! I realized that I had previously been wasting some of the dye.

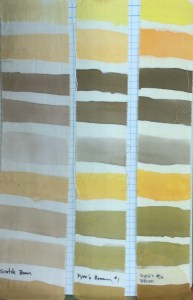

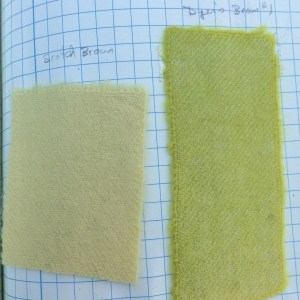

The fabric was dyed with the extracted liquid. The amount of dye ranged from 6.25% w.o.f. to 100% w.o.f. I also did exhaust baths of the dye.

Madder is an interesting dye because it contains so many different colorants. The alizarin is what gives us the red, but it also contains other colorants: yellow, orange an brown. The initial dye at each depth of shade was dominated by the red. Exhaust baths contained less red, while the orange dominated. The colors obtained from the initial dyeing at 50% w.o.f. and 100% w.o.f.were very similar but the stronger bath continued to give me red before the color turned more orange.

The test was repeated on wool with similar results.

Dye extracts are what drew me back into natural dyeing but I’m finding that working with plant material is far more compelling. Each plant and dyestuff is unique and since these are natural products they are subject to the changes in growing seasons and processing. Testing my dyes in order to understand the nuances is time well spent. It will make me a better dyer.