© Catharine Ellis, as posted to the blog: Natural Dye: Experiments and Results

Fermentation vats are the oldest method of reducing indigo. These vats rely on the effect of bacteria present in an alkaline environment to cause the reduction that will allow the indigo molecule to become soluble. The bacteria existing in an oxygen-free environment is referred to as anaerobic. An indigo vat is reduced in anaerobic conditions.

A “sukumo” vat, traditional in Japan, is a fermented vat that uses composted indigo leaves from the polygonum tinctorium plant as a source of the dye plus cellulose plant material that will help feed the vat. A sukumo vat contains no added indigo pigment. The preparation of sukumo is a lengthy process requiring the composting of indigo leaves after they have been harvested and carefully air dried.

For those of us who do not have access to sukumo, it is important to know that a fermented vat can also be made using indigo pigment. This is the approach that was often used by 18th century commercial dye workshops in Europe. Since the pigment is inert, suitable sources of bacteria and “food” for that bacteria must be added to the vat.

• Advantages of the fermented vat: A fermented vat uses a lower pH (9.5-11) versus the quick reduction vats, which makes it suitable for both protein and cellulose fibers. The correct pH of a fermentation vat can be obtained using wood ash lye, soda ash, or potash. Only small amounts of lime are used throughout the life of the vat to maintain a correct pH. These vats are suitable for long-term use, provided they are maintained correctly. That is something that will be covered.

• Challenges of the fermented vat: Typically, the vat requires 7 -14 days to reach full reduction, but I have seen it take as long as 30 days. The vats must be carefully monitored and maintained by making regular additions of lime and organic material to maintain appropriate pH levels and insure a continuous source of bacteria.

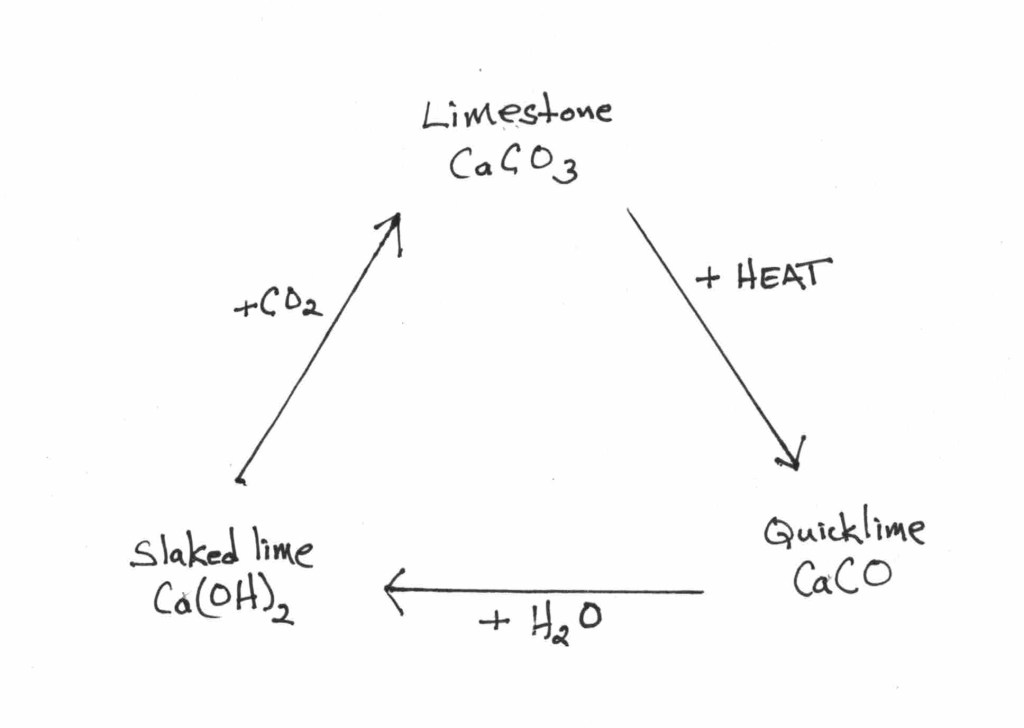

Quick Reduction vats, though used historically, were re-introduced to contemporary dyers by Michel Garcia and have gained great popularity amongst contemporary practitioners. These are the vats that we presented in The Art and Science of Natural Dyeing. They are easy to make. They rely on the use of sugars, fruits, plants, or minerals and require a very alkaline environment (pH 11-13) to achieve reduction. This high pH necessitates the use of significant amounts of lime (calcium hydroxide) as an alkali.

• Advantages: These vats reduce quickly – usually in a day (or less). They use no harmful chemicals, though they do require working with a very alkaline substance and solution. Vats made with reducing sugars can be kept for several weeks and, with careful and regular maintenance, can be used for several months.

• Challenges: The high pH is not suitable for all fibers (a high pH will damage protein). The large quantity of lime (calcium hydroxide) used to achieve the pH builds up quickly in the vat. The lime is also very difficult to remove from the finished textile and can compromise the dye and color, possibly resulting in “unexplained” fading of the blue.

Chemical Vats use either sodium hydrosulfite or thiourea dioxide to reduce the indigo molecule. This process is used extensively in industry, and I know that some hand dyers also use this process, as it is very predictable.

• Advantages: Complete reduction takes place very quickly – usually within minutes. The pH of the vat is 10-11.

• Challenges: Reduction chemicals can potentially have a very detrimental effect on the lungs and health of the dyer. When used in combination with a high pH, they can also damage the tactile qualities of wool fibers. Personally, I do not like the smell of the chemicals.

Because reduction is so complete using reduction chemicals, it can be challenging to achieve pale colors when using chemical reduction. It is also difficult to use multiple immersions in the vat to increase the depth of shade, as repeated immersions will re-dissolve the indigo already incorporated in the textile.