Last week I received several questions about how to finish textiles after dyeing with indigo. What now comes naturally to me, I realize, is not well understood by all dyers.

First, back to the dyeing: the textile should be dyed in long immersion baths (10-20 minutes). Without the long immersion, the dye will only sit on the surface of the textile and will not be lightfast.

Once the dyeing has been completed (and all the dye has oxidized) the textile must be neutralized. There is a great deal of alkalinity in the fibers from the calcium hydroxide (lime, calx) and that requires neutralization. Without this step, the textile will be vulnerable to damage. It will yellow over time and it won’t have a good hand.

Many years ago, I made the assumption that only protein fibers needed to be neutralized. That is definitely NOT the case. All fibers must be neutralized!

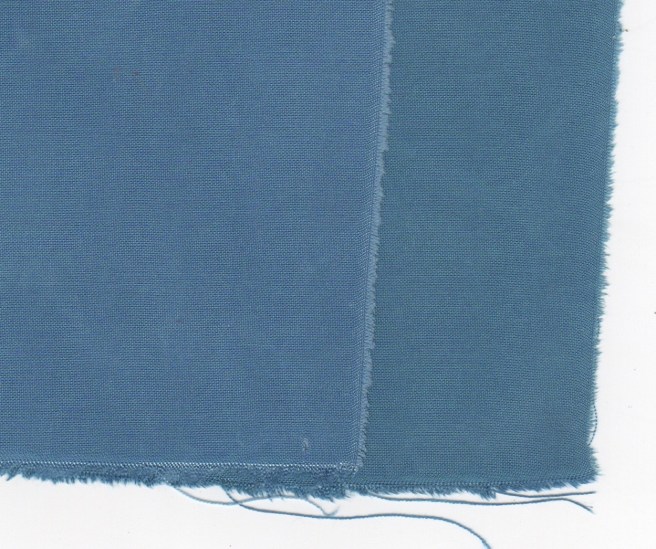

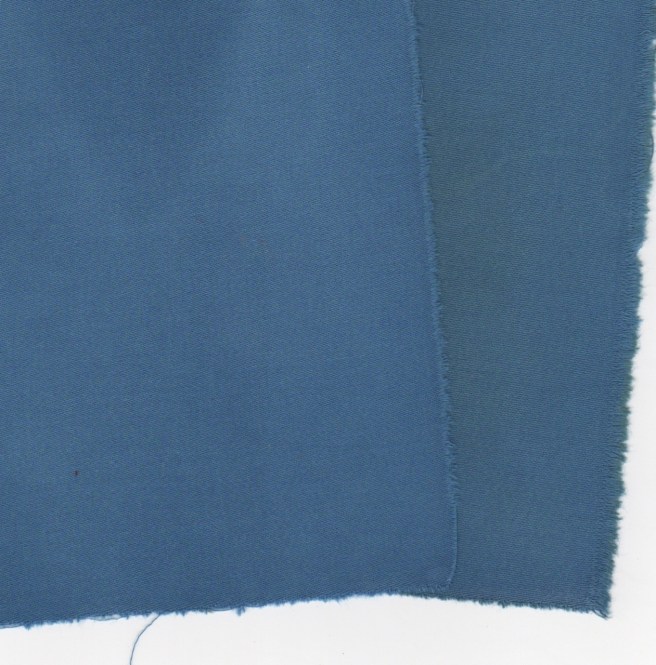

Neutralization takes place in a water bath, to which a few “glugs’ of white vinegar (5% acetic acid) have been added. This is equivalent to about 1 tablespoon (10 ml.) per liter of water. Allow the textile to soak in the vinegar bath long enough for the acid to fully penetrate into the fiber (a few minutes to one hour, depending on the density of the textile). You can actually see the color brighten during this step.

Next, the textile must have all excess dye completely removed. The best way to do this is in a heated bath, to which a small amount of pH neutral detergent is added. Heating will cause the vat dye molecules in the fiber to combine into larger units, making them stronger, while also removing excess dye that has not attached to the fiber. Boil cellulose for about 10 minutes. Protein fibers can be heated to an appropriate temperature and maintained at that temperature for about 10 minutes. After this step a thorough rinsing should be performed. THAT’S HOW TO FINISH INDIGO!

How did I come to understand all of this? I would still be wondering about much of it without my friend and colleague, Joy Boutrup. Joy is a Danish textile chemist, engineer and creative thinker. In an earlier post, I mentioned that we have taught together many times at Penland School of Crafts. Joy has helped me to understand process and the reasons behind the process. In its most recent issue, Fiber Art Now magazine has published a wonderful article about Joy, written by Lasse Antonsen. I encourage you to read it here.

Joy and I are currently writing a book on natural dyeing! It will be a practical handbook for dyers, which not only explains HOW to dye but WHAT is happening in the process and WHY we might choose one process over another. Schiffer Publishing Co. will publish the book. Release date is targeted for late 2018.

As I work through studio processes and words of explanation for the book, I realize how much I have learned from Joy’s deep understanding and perspective and I value her as a collaborator. Our book should help all of us to become better dyers.