I am a natural dyer but I also enjoy reading about and cooking food. I was recently perusing Michael Ruhlman’s book, Twenty: 20 Techniques, 100 Recipes. The first chapter is titled “THINK: Where Cooking Begins”. The author talks about the importance of thinking to the cook. I might say the same thing about the dye kitchen. Dyeing is not just about following a recipe, but thinking about and understanding the role of each of the ingredients.

Ruhlman recognizes that his list of techniques includes many that are also ingredients: salt, acid, sugar… One might say the same thing about our dye ingredients: mordant, acid, base, or dye plant… Awareness of what each ingredient contributes to the process is key to understanding how it fits into the larger picture of dyeing.

Let’s talk about mordants – alum specifically.

The alum we typically use in the dye studio is potassium aluminum sulfate [KAl(SO4)]. It is most likely made in a laboratory, is in powder or small crystal form, dissolves easily, and contains no contaminants such as iron.

Aluminum sulfate [Al2(SO4)3] is made by a different process and may be contaminated with small amounts or iron. The first dyeing I ever did utilized naturally occurring alum gathered from the ground surface – no telling how impure or contaminated it was.

We often shorten the name of our mordant to simply “alum” but there are many different types of alum and it may be best to use (and specify) potassium aluminum sulfate. I never purchase from a supplier who cannot provide material with that specific name.

Potassium aluminum sulfate bonds with the dyestuff and makes an insoluble lake INSIDE the fiber. Without this insoluble bond, the dye can wash out. This is why we don’t put dye, alum, and fiber in the same pot; inevitably some of the dye will bind with the alum in the bath OUTSIDE the fiber. That would be a waste of our dye and mordant.

The traditional approach to mordanting and dyeing is broken down into two steps. 1.) The alum is applied to the fiber. 2.) The fiber is dyed in a second bath, attaching the dye to the mordant and making the lake inside the fiber.

It’s important to get the mordant INSIDE the fiber. That is why we pre-wet and heat wool so that the scales will open up and the mordant goes inside. Otherwise we have ring dyeing, with the mordant and dye just sitting on the surface.

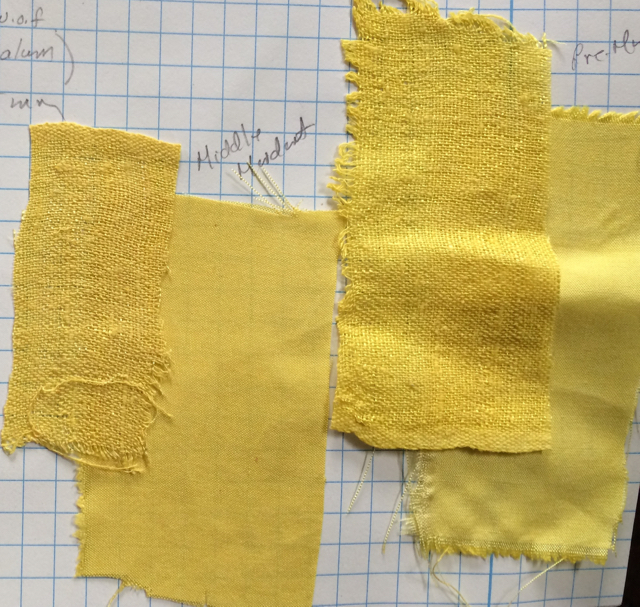

I have lately learned to dye silk using the Japanese approach of “middle mordanting” with Dr. Kazuki Yamazaki. The fiber is first dyed, then mordanted, and then re-immersed in the dye. This approach didn’t make a lot of sense to me until I experienced it and observed that it accomplished the same thing as pre-mordanting. The dye and mordant still go into the fiber and make the insoluble lake there. It’s a slower, quieter process which has the potential of building up layers of mordant and dye on the silk. This process is not suitable for wool.

Some things to THINK about:

- Alum is acidic – a useful thing to remember.

- Once a fiber is mordanted, it is always mordanted. The mordanted fiber can be dried and stored indefinitely.

- The more dye there is, the more mordant is needed.

- Alum can be removed with a stronger acid, such as citric acid.

- I typically use my alum at 15% of the fiber weight but I always test a new source of mordant in order to be sure that the strength is the same. Test by mordanting, dyeing, and observing.

- Potassium aluminum sulfate is an excellent mordant for protein fibers. I would take a different approach to mordanting cellulose.

- When a dye lake is made OUTSIDE the fiber it results in an insoluble pigment.

- When a dye lake is made INSIDE the fiber it results in an insoluble pigment.

- How the mordant and dye are applied to the fiber is very important.