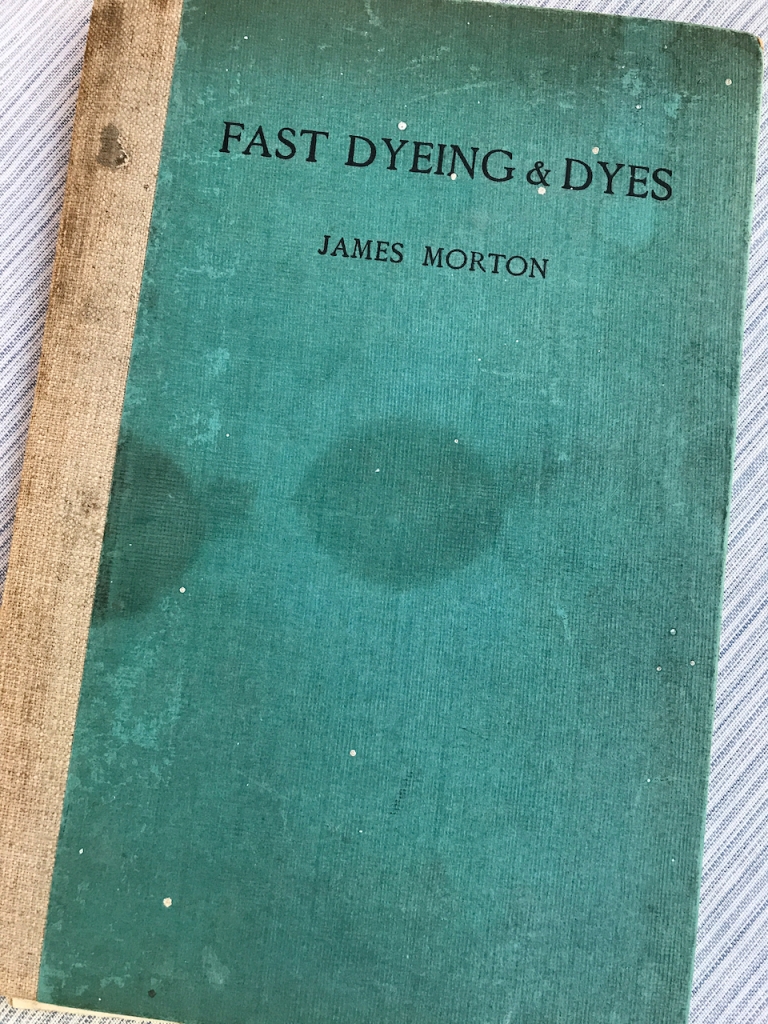

A dear friend recently put a small booklet into my hands: Fast Dyeing and Dyes by James Morton. It is the bound proceedings of a lecture that Morton delivered to the Royal Society of Arts in London, 1929.

Morton’s father, Alexander Morton, founded the weaving company of Alexander Morton & Co, in England in the late 19th century. The son, James was trained as a chemist and specialized in the use of permanent lightfast dyes for cellulose textiles. In the narrative, James recounts work that he accomplished in 1903 to develop a palette of lightfast dyes for textiles. It was an interesting time in the development and use of textile dyes. Up until the second half of the 19th century, natural plant and insect dyes were the source of all textile colors, but by the early 20th century chemical dyes were quickly replacing the natural dyes in industry.

Morton’s company specialized in producing woven furnishing fabrics for curtains, carpets, upholstery and tapestries. He spoke of observing one of the company’s tapestries in a store window display. After only a week’s time, the colors had faded dramatically. This led him to question the dyes they were using. He commandeered his family greenhouse (which had previously contained tomato plants) to set up a series of lightfastness tests. He tested fabrics from his own company as well as those from others. The results he described as “staggering”. Even deep shades of color applied to expensive fabrics became almost white after only a week’s time. He made detailed notes and documented each sample.

After making these careful observations, his goal became one of identifying a few colors (produced by chemistry) that could be relied upon and that performed well. Morton believed that even a limited range of colors that would remain on the textile over time was far preferable to a large palette of color that would degrade quickly. The company trademark Soundour was born – a combination of the word “sun” and the Scottish word “dour” meaning stubborn or hard to move. He identified the Alizarines as “good friends” which kept their shades. This was a class of chemical dye, based on the synthetic manufacturing of alizarin, the primary red colorant in madder root. In 1869 it was the first natural dye to be produced synthetically. Colors derived from minerals were acceptable as sources for light browns. Indigo was deemed unsatisfactory for longevity on cellulose but Indanthrene vat dyes, new to the market, served as a good source of yellows, blues and greys. (These are the same vat dyes that I previously used in my own work.)

All the chosen chemical dyes were tested thoroughly, both in the greenhouse and on rooftops in India, where the sun was hot and intense and the humidity was high. The result was a carefully chosen palette of color that could be advertised as reliable and be priced accordingly – significantly higher priced than other fabrics on the market. The goal was to have colors that would last as long as the textile itself.

What strikes me about this story is the recognition of lightfastness being of value at a time when there was such excitement about the ability to easily produce almost any color through the use of the new “chemical” dyes. Morton changed the industry’s awareness of and approach to the use of synthetic dye color. Interestingly, he stated that “Some manufacturers questioned the wisdom of raising the standards so high…”

I can’t help but see a parallel to today’s re-discovery and excitement about natural colors. That excitement often causes a “blind spot” when it comes to objectively looking at the longevity of some dyes. If the experience of making color is the singular goal then it doesn’t matter so much how long the color will ultimately last, but if there is a customer with an expectation that the color will last as long as the textile, then colorfastness is a different and critical matter.

Professional natural dyers have made decisions over the centuries to provide customers with the best quality colors possible. The Dyer’s Handbook: Memoirs of an 18th -century Master Colourist, by Dominique Cardon makes the following statement about testing for “false” colors: “It is not enough for the dyer to have acquired knowledge on the drugs that are necessary to him and on their properties, and to have managed to employ them with success. He must also distinguish the fast colors from the false ones…”

All dyes fade – that’s a fact. And all textiles will deteriorate. My colleague, Joy Boutrup, says that acceptable fading of a dye results in a lighter version of the original hue while the integrity of the original color is maintained: a lighter indigo blue, a softer madder red etc. – not an “ugly beige color” that has no relationship to the original. And the ultimate goal is that the color last as long as the textile.

Informative article Thanks Mukesh kanabar

On Tue 4 Aug, 2020, 15:43 Natural Dye: Experiments and Results, wrote:

> Catharine Ellis posted: ” A dear friend recently put a small booklet into > my hands: Fast Dyeing and Dyes by James Morton. It is the bound > proceedings of a lecture that Morton delivered to the Royal Society of Arts > in London, 1929. Morton’s father, Alexander Morton, found” >

Fascinating story! And I agree, the situations resemble each other. Those ”grand teint” shades of indigo, cochinelle, madder and weld truly have stood the test of times. However, it is good to also rediscover some local natural dyes, that do not need to be imported. The measurement of the dye lasting as long as the textile is a good one. 🧶

Thank you for this interesting article. It gently puts some of the present praiseworthy enthusiasm into prospective. The traditional dyes have well stood the test of time and of course one must always explore a little further, it is in the very nature of all who work with plants and dyes, is it not? I am all for the idea of people knowing that this is dyed with so and so and it will fade graciously but I do however sometimes worry about the reputation of natural dyes when I see some things on offer nowadays which are obviously going to fade fast and cause unexpected disappointment .

Thank you, great post

Janet sustainable styling, sustainable textiles http://www.janetmajorimage.co.uk http://www.imagejem.blogspot.co.uk 07990 702223 sent from my iPad

>

Fascinating.

The mine field of natural dyes, then when you add washfastness into the mix it is even more difficult, indigo being a good example of a lightfast dye but poor washfastness. Of the classics, weld is the stronger yellow but fades more quickly than madder or indigo. Also, we wash our clothes more frequently than in the 1800s. It would be good to have a chart to manage expectations. So much to ponder!

Very interesting article on the search for lightfast dyes. Your samples are noteworthy. I wish logwood would keep its beauty but unfortunately wishing doesn’t help. I agree that fading of the original color to a softer shade is acceptable and even to be desired at times. I remember the Madras plaids of my youth. You weren’t “cool” unless they were faded.

A very timely article!

Fascinating! History teaches us so much, if we care to listen.

Great information. Thanks so much for sharing it.