We headed out recently for, what has become, our annual trip to New England. I always try to include a stop at a “place of interest”. Last year I contacted Winona Quigley at Green Matters Natural Dye Company in Pennsylvania. She was very welcoming and I was pretty much in “awe” of what she was doing there and, as a result, didn’t make a single note, or take a single picture.

This year, I arranged to stop by again, with the idea of documenting her operation a bit and sharing her story.

Green Matters Natural Dye Company is a small scale dye house that uses natural dyes exclusively to dye garments for their customers.

Winona Quigley, founder and owner of the company, studied fashion at Parsons but she has been thinking about sustainability and natural dyeing for a long time. When it came time for her to do a “capstone” project, she wanted to design a line of naturally dyed clothing. This eventually evolved into The Green Matters Natural Dye Company, which began its first dyeing in pots at Winona’s mother’s house in Lancaster County PA 10 years ago. The current location of the dyeworks is still in Lancaster PA, an area known for its beautiful farms and agriculture, and where a horse and buggy is a common site on the road. But the dyeing here is all small scale industrial.

The Dye Works operation is approached from the back of the building and truly looks like a small industry. The telltale sign that we had found the right place was the buckets of avocado pits, which looked like they’s been cooked to extract their color.

The company does some work with designers to develop small lines of custom natural colored garments but a very popular and important focus is the “Dye Color of the Month” program. Dye color blends are developed by the dye team and are most often an interesting mix of more than one dye plant (such as “rum raisin” made from cutch and madder or “ochre made from cutch and weld). Customers send in their own clothing (and even bed linens) which can be given a renewed life with a fresh, naturally sourced color. The dye team will unpack the garment, mordant when needed, and then apply the chosen dye color(s). Colors are sourced from both plant materials and natural dye extracts. Tie-dyeing is also an option, either in the initial garment dyeing, or as a more subtle post dye process.

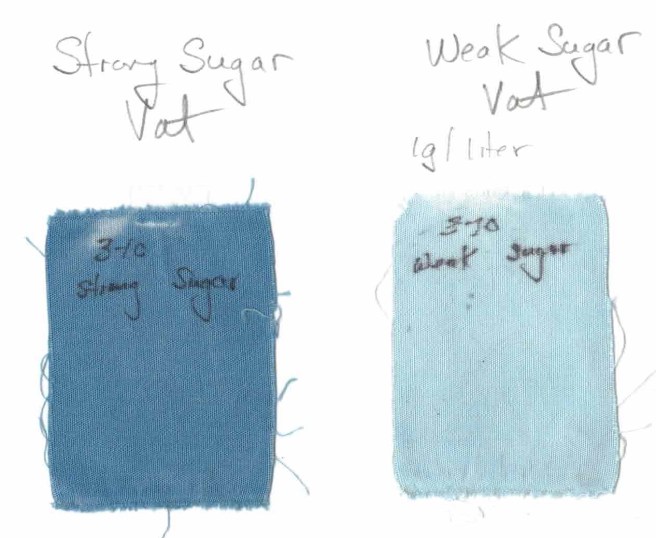

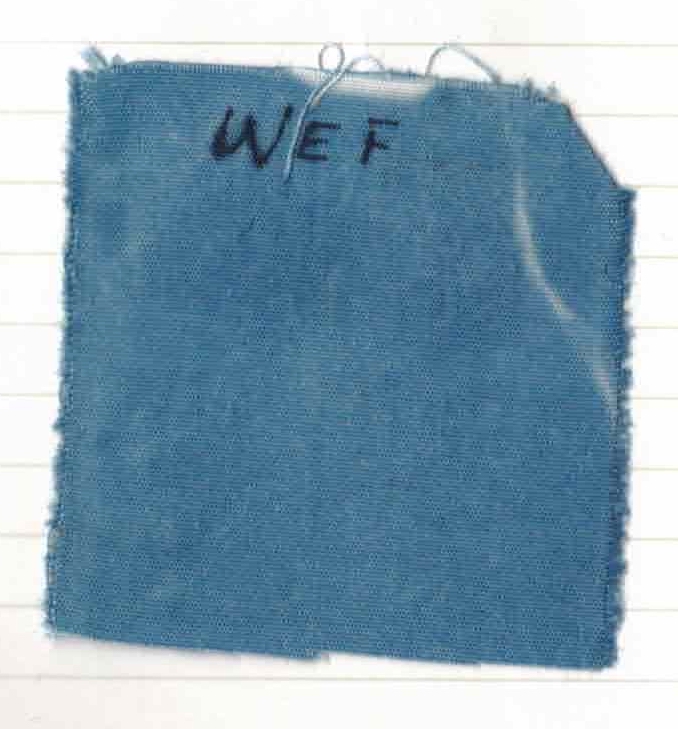

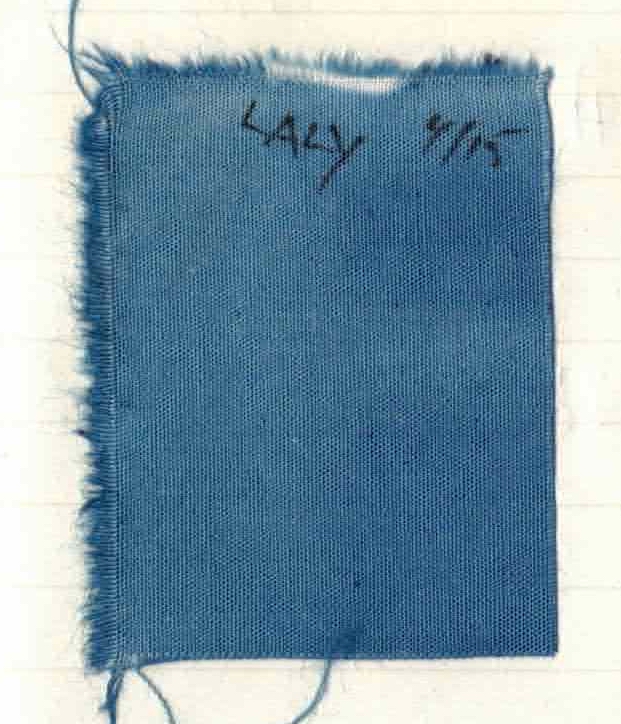

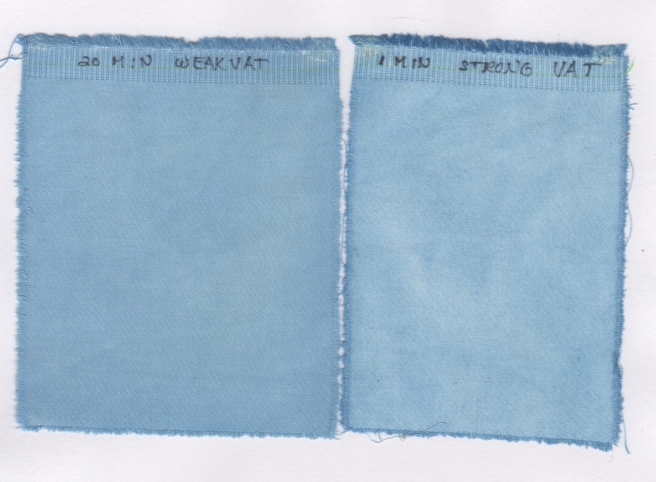

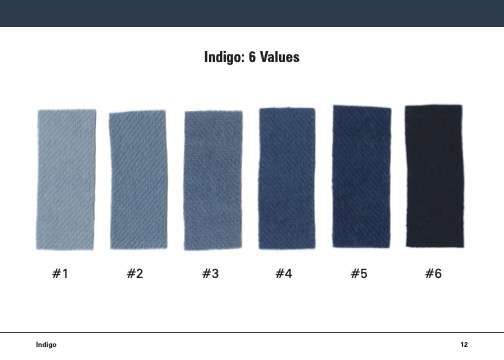

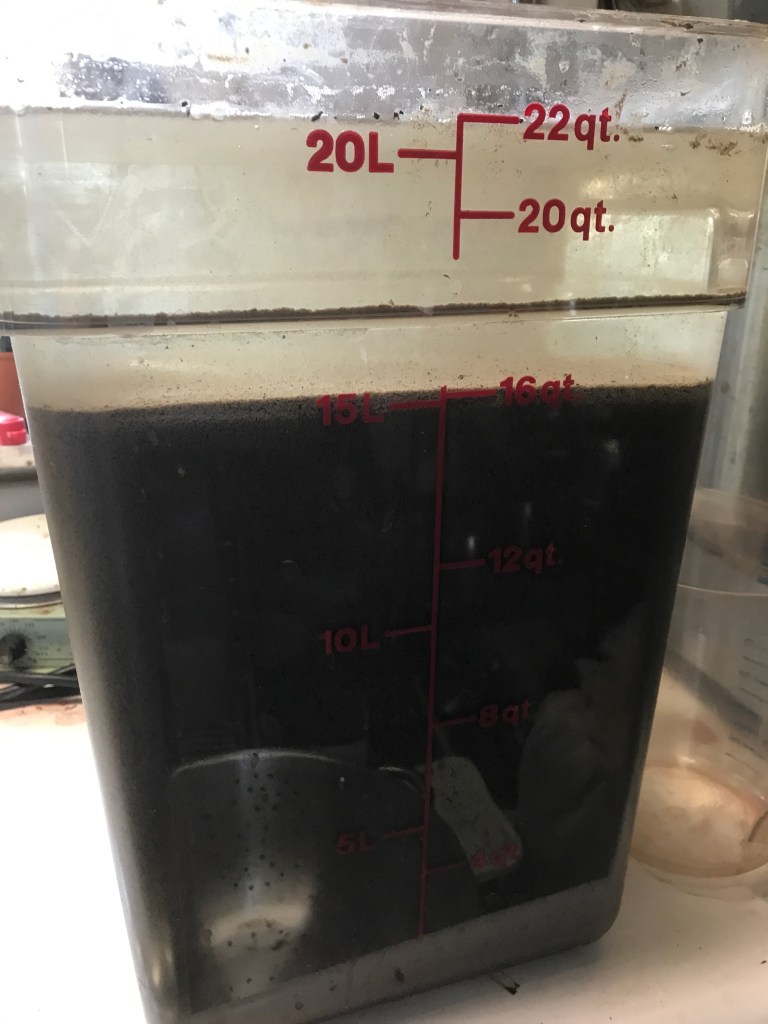

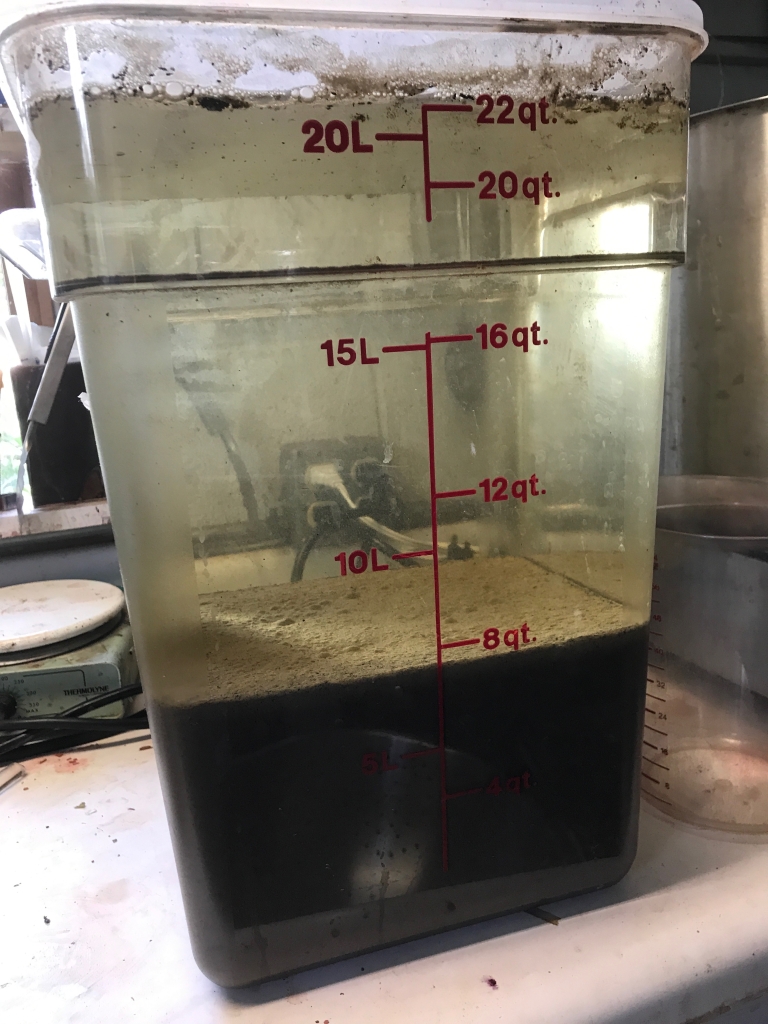

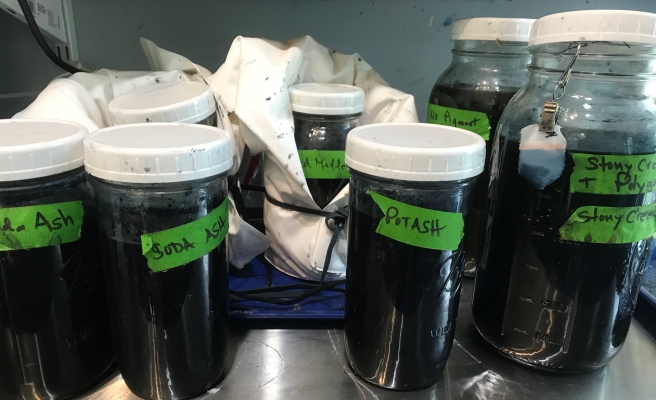

Each garment is dyed individually in indigo by Cara in an iron vat, and then carefully hosed off (with rain water) to rinse between immersions in the vat. Color mixes often include very carefully dyed shades of indigo, followed by mordanting and subsequent dyeing.

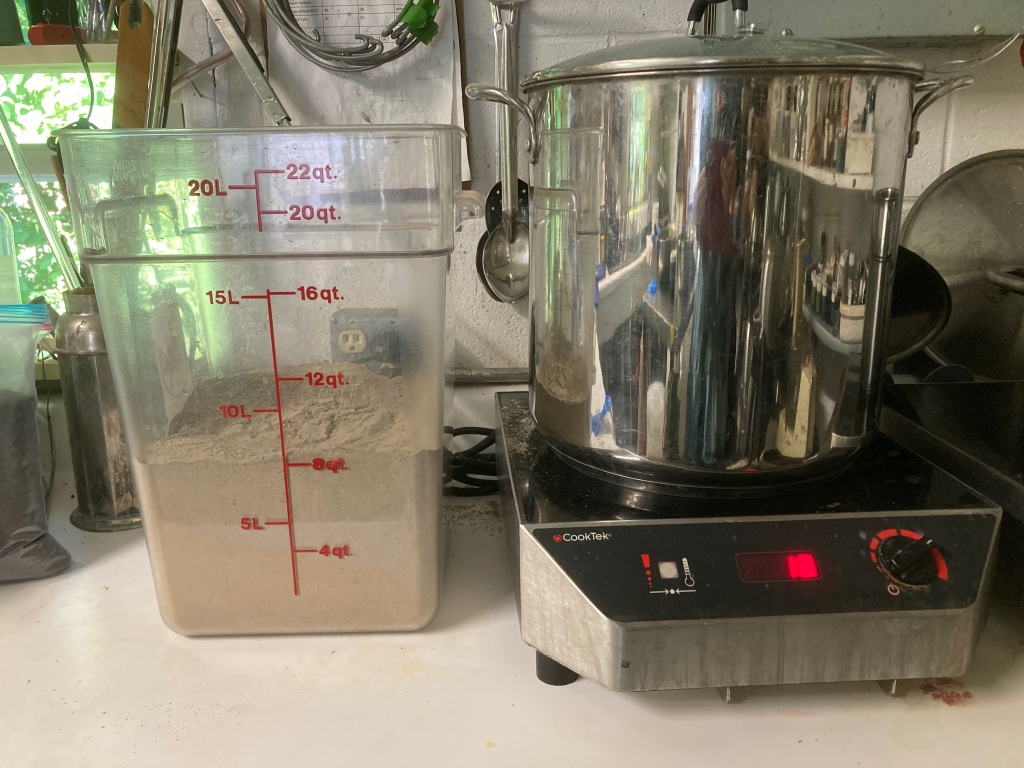

Mordants and mordant dyes are applied in small dyeing “machines,” like open top washing machines. These particular machines were custom fabricated for a small industry but were never used. Green Matters located them in storage when they were ready to expand from using dyepots at Winona’s mother’s home to their current location. The machines keep the garments in continuous motion, assuring the most even mordanting and dyeing possible. This kind of piece dyeing is impossible to do well in a studio dye pot. Much more sophisticated machines are used in industry today but these older machines do the job well.

The concept of refreshing our old garments with color is smart. If you are like me, we all have too many clothes. Some of them are loved, and will continue to serve us with a little “tweaking”. You may have a well-made and cherished garment, but it’s faded, sun bleached, stained, etc. Perhaps its light color is not practical for gardening, farming, or working in the studio. Vintage garments can be given a new life with a contemporary color. Re-dyeing is making a conscious choice by countering the pervasiveness of fast fashion. I often re-dye garments myself but am always plagued by the issue of uneven dyeing, as I am limited to dyeing in pots.

Water used for dyeing is all rain water, collected in cisterns underneath the building. The dye machines, which are energy efficient, use the same motor as a dairy mixer, and are easily maintained in a farming community.

Several things that truly impressed me:

- Choice of dyes. Green Matters seems to consistently make good choices about which dyes to use for the most long lasting colors. And they are combined in beautiful ways.

- The use of rain water. We all know that dyeing requires LOTS of water at every step. Doing this using a renewable resource not only saves $$ but is just smart!

- The re-purposing of dye machines and the ability to keep them maintained and working.

So, do consider sending a favorite natural fiber garment to Green Matters for a “facelift”. Far better that we promote a company such as this, than purchase yet another garment. Here is where to learn everything you need to know. Invest in a new color for yourself! The ordering process is easy, the choices are clear, and they will send you a mailing label to ship off your garment. And occasionally, Green Matters hold in-person classes, where perhaps you can dye your own clothing.

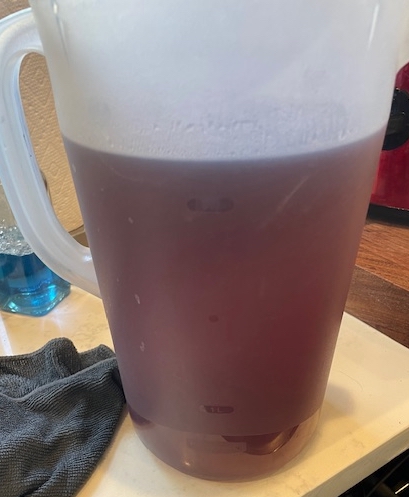

In order to truly understand how the process with Green Matters Dye Company plays out, I brought a favorite skirt of my daughters – it WAS pink and stained and thus she never wore it. She had asked me to dye it but I don’t have a pot big enough to even hope to get it dyed well. Green Matters Dye Company sent it back to us transformed, dyed in “rum raisin”, which is a combination of cutch and madder and lightly treated with iron in a “tie dyed” design, in order to further camouflage the original staining. This post dye treatment is an option. Now it’s a skirt that she loves to wear – and it even came with care instructions.

If you are looking for a sustainable gift for a special someone this holiday season, consider gifting a dye lot. It will come with all you need to ship off a garment and give it a new life.