© Catharine Ellis, as posted to the blog: Natural Dye: Experiments and Results

Determine the size of your indigo vat:

This decision is primarily based on your intended use of the vat. If the vat is made for only small scale test dyeing, perhaps a 1-liter jar is adequate. Larger test dyeing and the dyeing of small pieces can likely be done in a 5-gallon bucket (approximately 18 liters). If you wish to dye garments, multiple skeins of yarn, or fabrics, I think the minimum size for good dyeing is approximately 50 liters.

Importantly, undissolved materials (lime, bran, etc.) will build up over time in the bottom of the vat, leaving only the upper portion of the vat available for dyeing. Fourteen gallon plastic drums can be sourced, from a variety of suppliers, which are significantly taller than they are wide, allowing plenty of room at the top of the vat for good dyeing, while allowing the solid materials to settle to the bottom half of the vessel.

It is highly recommended that the dyer who is new to the use of fermented indigo vats begin with small (one liter) test vats to become familiar with and confident with the process before moving on to a large vat.

Once successfully reduced, test vat(s) can be used to “seed” a larger vat when you are ready to build one for serious dyeing. “Seeding” a larger vat in this way will stimulate bacteria growth and can significantly decrease the time required for the larger vat to reduce.

Small test vats can also be added to older vats that have decreased in volume from evaporation or just the process of dyeing.

Water:

It’s important to consider the source of your water. Is it acidic? neutral? City water may have chlorine incorporated, which will inhibit the growth of bacteria needed for the vat. The amount of chlorine can be influenced by the distance from the chlorination facility as chlorine will dissipate. If your water is chlorinated or smells of chlorine, there are three ways that can be used to remove it:

• Boil the water for 15 minutes to release the chlorine.

• Leave the water in an open container at room temperature for 24 hours.

• The use of filtration systems can also be used to remove chlorine.

How long will it take for the vat to reduce and begin dyeing?

My vats will typically reduce and begin giving me a full, clear indigo blue after 7-14 days. But I have seen it take as long as 40 days! Much of this depends on how well the vat is tended; temperature, pH, etc. You will only learn the length of time required for the vat to be ready by making that vat and by careful monitoring and testing. Trust me. You will know when it’s ready. Your test strips will be blue!

How long will a fermented vat last?

The life of a vat depends on:

- how much the vat is used for dyeing

- how much indigo is in the vat

- vat maintenance

- organic matter in the vat

I have had fermented vats that lasted 3 years or longer, with careful monitoring and maintenance. Over time, though, the solids will build up at the bottom of the vat, decreasing the usable solution that is available for dyeing in the upper portion of the vat. For this reason, many dyers will plan to use a vat for about 6-12 months and then discard it. I usually dispose old vats on the compost pile, but, after neutralization, the liquids can be put down the drain but it’s best to strain out any solids on the bottom.

The amount of indigo pigment used when making the initial vat will determine how long the vat can be used for dyeing. Counterintuitively, a vat that has 2 grams of indigo per liter will initially result in nearly the same depth of blue dye as one with 8 grams of indigo. I know that this sounds illogical but I know this from observation. Importantly, the vat with the lesser amount of dye will weaken sooner, as the dye gets used up, and result in pale blue colors. This can be very desirable, as the ability to achieve a pale blue is sometimes important for controlled color mixing. For this reason, I would recommend using smaller amounts of indigo (2 grams per liter) when the vat is begun. As the vat becomes weaker and results in pale colors, start a second vat to produce darker shades.

Does the fermented vat require heat?

I have found that the vat does best with supplemental heat (between 16°C/60°F and 30°C/85°F) in the initial stage while fermentation is starting. If the ambient temperature in the dye studio is warm enough, there is no reason for added heat. If supplemental heat is required, it’s best to use a heater that will surround the vessel. Avoid immersion bucket heaters, which can get too hot very and concentrated high temperatures can kill the live bacteria. Some form of temperature control is ideal. A plastic covered household heating pad, set on low, will work well for small vats. For larger vats, a bucket wrap heater with a thermostat is ideal. For this reason I use a temperature controller with an immersible probe. This will automatically turn the heater on and off to maintain an ideal temperature.

Once fermentation has been established and the vat is in reduction, ideally, you would maintain those same temperatures. But, I have found that it is not always necessary to continue to apply supplemental heat to the vat. I have maintained fermented vats successfully through the winter where the overnight ambient temperature in the studio is as low as 5°C/42°F. One winter I had two vats with heat and another without heat. All vats continued to dye well. But there may be better penetration of fibers with a warmer vat.

What form of indigo is used for the fermented vat?

The vats described here are made with extracted indigo pigment. I prefer to use natural indigo pigment, but the vat can also be made successfully using synthetic pigment. I have had success using dried indigo pigment or indigo paste pigment (pigment that has been freshly extracted and never dried). I assume that paste pigment may still contain bacteria that will aid in the reduction of the vat which is, obviously, a plus.

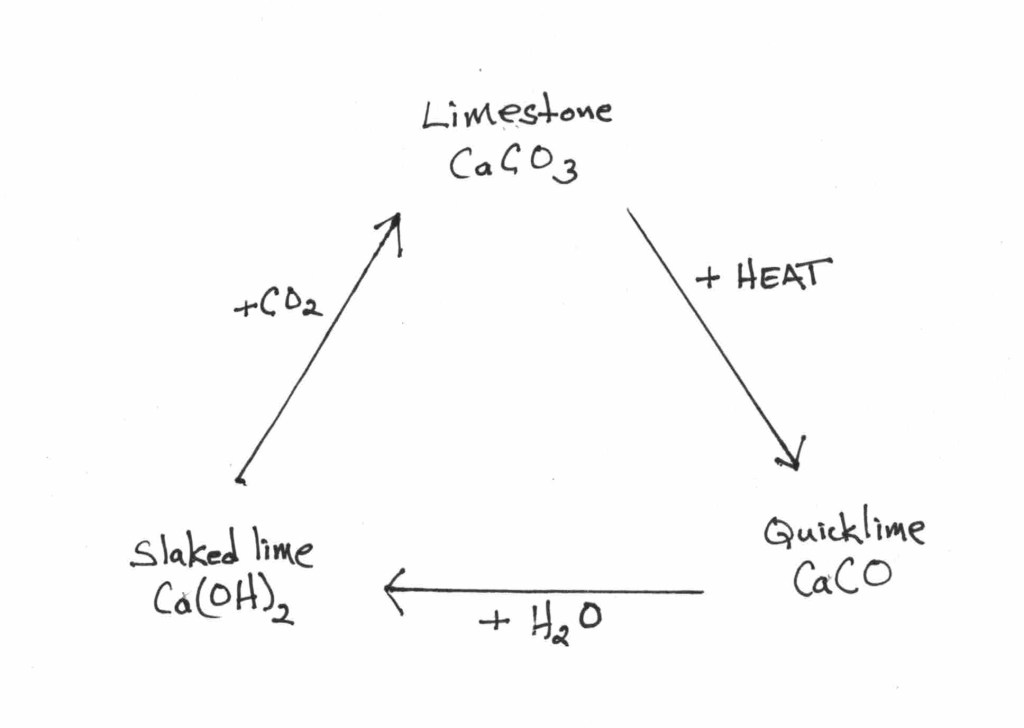

What is the source of alkalinity for the fermented vat?

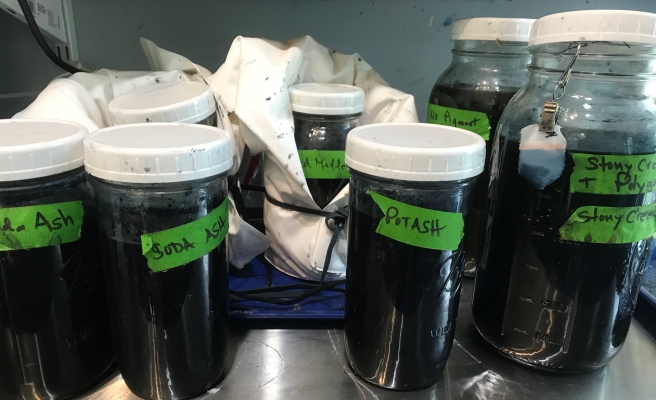

These vats can be successfully made using soda ash (sodium carbonate), potash (potassium carbonate) or wood ash lye, which is made from hardwood ashes. The processes of making wood ash lye will be described in a later blog post. From my research, it is suggested that soda ash or potash was typically used in European production workshops vats of the 18th and 19th century.

The maintenance of the vat requires the addition of very small amounts of lime (calcium hydroxide) to maintain the pH, since it is a much more potent alkaline substance.

What is the source of the bacteria used to reduce the fermented vat?

While composted sukumo is a source of indigo pigment, some of the bacteria, and of the plant material for bacterial growth, the vats made with extracted indigo pigment require additional organic material to begin and maintain the fermentation process.

• Wheat bran is a primary source of bacteria for the vat and is used for all fermented vats, including in the sukumo vat.

• In addition, the vat requires a source of “food” for the bacteria, which also contributes to the diversity of anaerobic bacteria in the vat.

• Traditional European dyers used “spent” madder root. This is finely ground madder root that has already been used for its red dye.

• Hisako Sumi, Japanese indigo dyer and researcher, recommends the use of dried indigofera tinctoria leaves as an alternative bacteria/food source for the vats. (I would speculate that these leaves also contain very small amounts of indigo precursors). The Indigofera tinctoria leaves are dried, finely ground and are often used for used as a dye for hair. The ground, dried leaves are sometimes referred to (and sold as) “black henna”, since a combination of henna and indigo powder will result in a natural black hair dye.

I have been successful using alternative plant materials and will go into that in more detail in a later blog post. Research and my own observation indicate that diverse sources of bacteria will help contribute to, and maintain, successful fermentation.

In addition to the madder root and/or dried indigofera tinctoria leaves used during the construction of the vat, other organic substances can be added to the vat and will contributes to the fermentation process and include:

- Woad balls can be made by grinding fresh leaves of the Isatis tinctoria plant, forming the balls and drying. These balls can also be “couched” or lightly composted by breaking them apart, adding a bit of water, and allowing them to ferment.

- Fresh leaves from Polygonum tinctorium or Indigofera sp. can be ground, formed into small “patties” and then dried. These also can be broken up and added to the vat.

Additional wheat bran is used on a regular basis to maintain fermentation throughout the life of the vat.

Does the fermented vat have an “odor”?

Yes! The vat has a distinct smell from the bacterial fermentation. The smell is also a useful indicator that the vat is “working”. This is not a sweet-smelling vat, such as a vat reduced with bananas or fructose. Personally, I do not find the odor unpleasant (once I got used to it!) but it is likely you will not want to keep this vat in a closed “living space” as you (or your housemate) may find it objectionable.

The NEXT post will have the first “instructions” for building a fermentation vat.