The short answer is “no” but here is the longer answer.

I’ve used Aleppo galls (either ground or extract) for years as my preferred tannin. They were recommended to me as being high in tannin and are readily available. Gall is a source of colorless, gallic tannin. I’ve done many tests comparing the Aleppo gall to tannins, such as sumac (from local leaves), myrobalan, tea, and many others but I had never compared different varieties of oak galls.

First of all, what is an oak gall? They are sometimes called “oak apples” and are small, round growths of plant tissue produced by the oak tree in response to the infestation and larvae of a wasp. There are many different species of wasps as well as oak trees. As a result, the galls from each of these is different. The Aleppo gall nut (Quercus infectoria) is hard and dense but can be ground to produce fine particles.

A friend from Missouri gave me a jar of her local gall nuts. She lives in a forest of white oak (Quercus alba) and gathers the galls when they fall to the ground. These galls have a smoother surface than the Aleppo but are just as hard and dense.

Recently I was in New England and was able to gather galls from the scarlet oak variety (Quercus cocinea). These are larger, very light in weight, and seemingly hollow. As a child, we referred to them as “puff balls”.

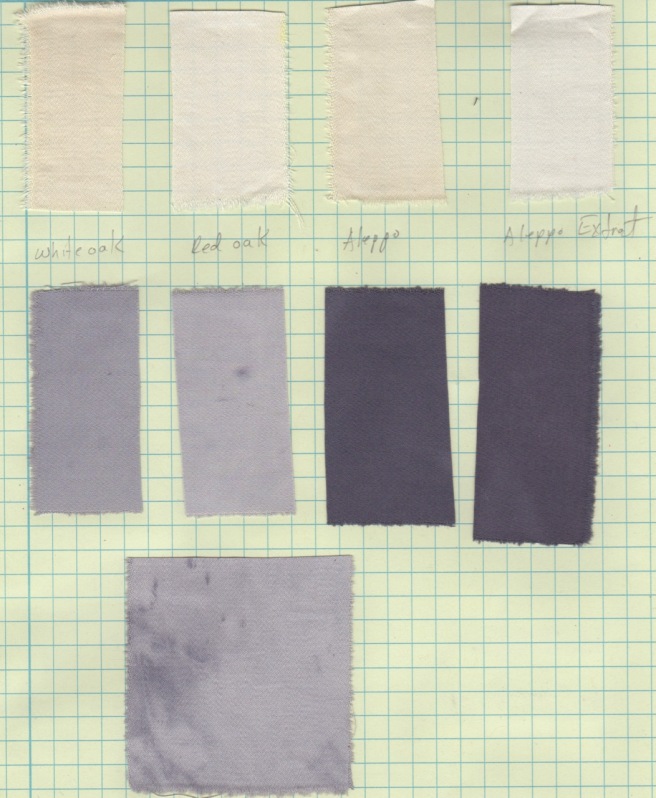

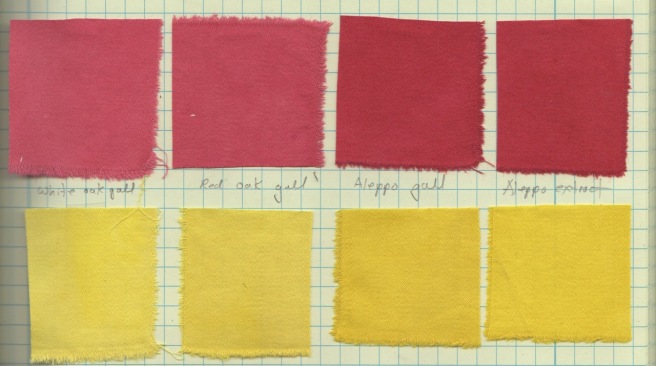

I wanted to know something about the tannin quantity of these various galls and if they could be used interchangeably for dyeing applications. They were applied to cotton fabric prior to mordant and dye. I used each of the tannins at 10% weight of fiber, which is the standard amount I use of gall nut extract.

The whole galls were ground with a small spice grinder, and further crushed using a mortar and pestle. Those from the White and Aleppo oaks broke down into fine granules, while the Scarlet oak variety was impossible to grind as fine, as the insides were truly “puffy” and “spongy”. Each of the ground gall varieties and the extract were put into warm water, using separate beakers for each, along with the cotton cloth. They sat at room temperature for 1 hour before the mordant was applied.

I took a portion of the samples with the tannin application and put them into a weak iron bath. When tannin and iron combine a dark grey or black will result. The shade of grey is an indication of the amount of tannin present. The Aleppo gall nuts, in either the ground or extract form, resulted in much deeper shades of grey than either the white or the red oak varieties. The large pieces from the scarlet oak resulted in a very uneven application of tannin. When the iron was applied, the surface was very splotchy and irregular.

The rest of the samples were then mordanted and subsequently dyed with both weld and madder. The amount of tannin has a direct effect on the amount of mordant that can attach to the textile, and the depth of dye color obtained is a direct reflection of the amount of mordant present. Based on the iron applications, I was surprised at the depth of the color obtained with all of the gall varieties. Although the dye color obtained from the white and scarlet oaks is lighter than the Aleppo, there is still significant color attached.

When using tannin prior to mordanting, it is likely that increasing the amount of gall from the white or scarlet oaks would increase the amount of mordant that attaches and thus the depth of dye color.

Locally harvested galls, when available, are an opportunity to use the local resources and achieve acceptable results.

The Art and The Science of Natural Dyes by Catharine Ellis and Joy Boutrup, available in late fall, is now available for pre-order.

Enjoyed reading your article and seeing your results

Thank you.

Thanks, Linda. It’s truly a journey!

HI linda,

Do you know if wattle galls are also a source of gallic acid. I am interested if they are useful in dye. I have access to a plentiful supply of these. Valerie

Wattle has been used in the leather tanning industry, and we know that the tannin content is high. But it is not a colorless tannin, such as gall nuts. I does impart a reddish color to a textile when combined with a mordant. I would certainly recommend that you use them and experiment.

Wow thanks so much for such a comprehensive trial! This is great. Regards, Anne

>

So interesting! Thank you, once again, for doing all this sleuthing work for us! So I would guess that we could just use a slightly higher concentration of the locally-gathered oak galls, say 15%, to get results comparable to the Aleppo variety?

Yes, I think so. I find that I need to use 30% of locally gathered dried sumac leaves to equal the gall nut extract. But any of these will give very acceptable results, even at 10%.

I’ll be trying sumac this fall!

Excellent information. Thank you.

Just love your way of experimenting and documenting. You mention mordanting after the tannin and iron baths before the dyebath. What mordant did you use or did you not specify because it is possible to use any of the mordants eg Alum, Tea, Rhubarb Leaf etc.

Alum would be the mordant. There are a couple approaches to using it for cellulose, but that’s too much information to go into here.

Excellent research, photos and information. I am in Australia and collect galls from a local Acacia species on nearby Kangaroo Island. I wonder how these galls compare with the varieties you have tested. I could send you some if you are interested. Thanks again.

HI Keryn, As much as I could be tempted to do another test, the information about local galls is far more relevant to a dyer in Australia. Or maybe someday I’ll find myself there with a need to know.

Thanks for the very interesting article – so much great information. Where do you purchase your oak gall nut extract? I’ve been looking for some to try. Maiwa is the only source I found and the postage is very expensive.

I purchase oak gall extract from Maiwa. With a $200 order they offer free shipping. Careful planning makes it relatively easy to make this minimum order.

Thank you. I have used Maia oak gallnut extract with great success in tanning fishskin. It becomes fish leather! Very lightweight but exceedingly strong. I came to your site hoping to find out HOW the extract is made & sold as a powder. It is far superior in my work compared to grinding oak galls or using a powder. The extract dissolves 100%. Do you know how they make the extract? Thank you. FiskurJoe

I believe that extracts are made by first making a decoction of the dyestuff (or tannin) and then the water is removed from that decoction. It’s a process that is best done in a refined laboratory setting. I first saw this video on Maiwa’s website. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gy5ySAtD8Lk

It was done by Coleur des Plantes and describes how a weld extract is made.

Thank you for that YouTube link to Maiwa. I had suspected it was very labor intensive. It is a great extract. I have ordered your book and looking forward to using it. Thanks.

I love this experiment. I have shared in our themazi dyes instagram many times.

Thanks for sharing this valuable results of your tests

Nice experiment and clear results. Thank you for sharing. Have you ever try willow gall?

Reblogged this on 2sheepinthecity's Blog and commented:

More inspiration if I ever dye again. xo